This is the third in a series of blogs about how to achieve more by rethinking failure. In this post I make a distinction about goal targets and goal benefits and explain how that leads to a new way to thinking about your challenge.

If we know one thing about goals, we know that taking on a goal means trying to reach a target. That’s the ‘S’ in SMART goals. That’s the ‘Specific’.

But hang on. That’s wrong already. When we take on a goal it’s not because we like to set targets, it’s because we want to get some benefit. So when do we get the benefit?

Is it all at once, when we achieve our target, or do we accrue it along the way?

Perhaps, because we see it so often in sport and competitions, we tend to think that all our goals have that same sharp division between getting a lot of benefit and getting a lot of pain. If we don’t reach the goal then, we’ve not only failed, but worse – the whole challenge has been a waste of time. But is that really the case?

UNDERSTANDING FAILURE LEADS TO A NEW WAY TO THINK ABOUT SUCCESS

Recently I was down in Wanaka and, wanting to go for a run, found myself at the start of the track that leads up to Royd’s Peak. The information board in the carpark said it was 8km to the top. In fact you could look up and see the route taking switch back after switch back, until there, above the snow line, above the yaks, above the Sherpas, blowing up in the Jetstream, the jagged summit of the mountain. It was getting late in the day – but I thought I would set myself the goal of getting to the top.

I didn’t make it. It was getting dark when I got to the final ridge line and so I turned back a few hundred metres from the summit.

Let me ask you a question - did I fail?

Really? Isn’t the opposite point of view also true?

Whatever answer you picked you’re right, and doesn’t that already give you a hint that there is something unhelpful about the way we think about goals and achievement? Why isn’t it bleeding obvious?

Here’s my go at untangling it. I think that the answer is ‘Yes I did fail’. Success was reaching the top and I didn’t reach the top.

Let me ask you a much better question. If I had known that I wasn’t going to reach the top should I still have taken on the challenge?

To figure out the answer you’ve got to know what the benefits are, because achieving ‘success’, that is reaching the target, is not the same thing as the ‘benefits’.

I was going for a run to burn off some energy, see some fantastic views and get fitter. Those were my benefits – getting to the top was my target. Regardless of the target every step I took up the track I got the benefits.

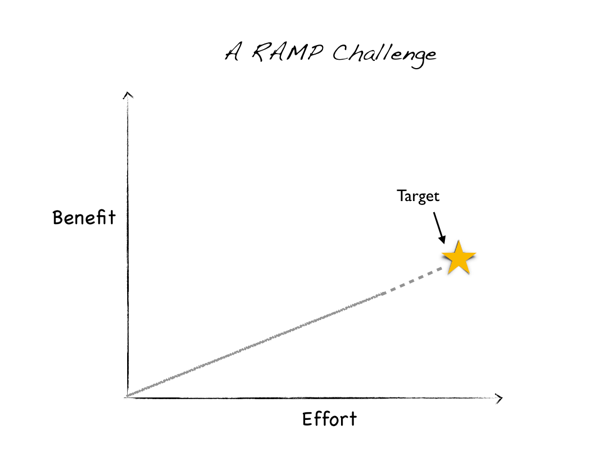

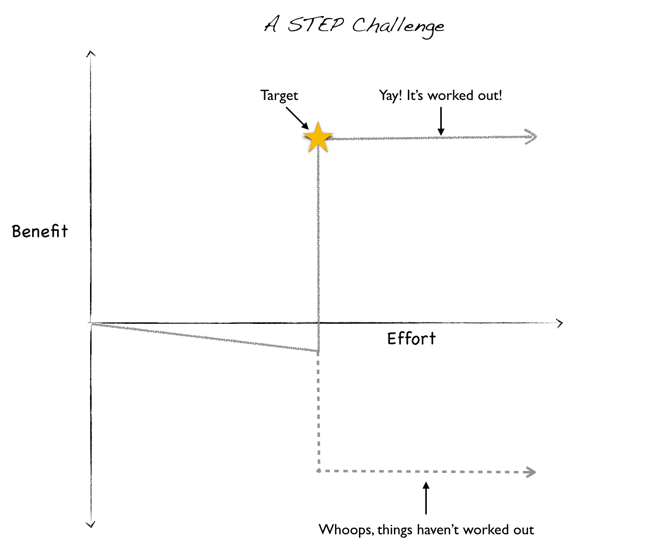

You can characterise your challenge based on the relationship between effort in and benefit out. Most goals fall into only two camps, RAMPs and STEPs.

For most challenges the more effort the more benefit. These are things like getting fit, losing weight, saving money, learning a language, or jogging up a peak. Let’s call these RAMPS.

(If you think that this point is obvious then why is the pile in your in-tray so big and your garage such a mess? ;-)

In some cases, though, there is a sharp line between success and failure. Like if you’re in the business of doing backflips on a motorbike, being shot from a cannon into a net, if you work as a blind knife thrower’s assistant or defuse bombs, or if you find yourself playing that weird Mayan ball game where they sacrifice the losing team.

For these types of challenges, things are pretty normal until a moment of performance when you either get all the benefit or you don’t. Let’s call these type of challenges STEPS.

I’ll give you some goals and you can tell me if they are RAMP or STEP. (Hint: If you fall a little short of reaching your target but you’re only a little worse off then it’s a RAMP. If you are much worse off it’s a STEP.

· Tight rope walking the Niagara Falls.

· Tight rope walking with safety leash across the Niagara Falls

· Playing Lotto.

· Losing weight

· Studying for an exam

· Making your sales targets

· Quitting smoking

Answers are:

STEP

RAMP

STEP

RAMP

RAMP

Quitting smoking – I’m calling it a RAMP because even if you aren’t successful quitting you at least had fewer cigarettes for some time. And given that the average smoker quits about 7 times before they finally stop, then you probably learnt something about quitting as well. On the other hand, if this is your last attempt to quit smoking then it’s a STEP.

WE THINK OUR CHALLENGES ARE STEPS – THEY MOSTLY AREN’T

(Hmmm, that was supposed to be a person in a cash grab booth!)

Most goals that we take on in real life are not do or die, winner take all STEP goals. In most of the actual goals we take on in life the more we achieve the better off we are, if we miss our target by 1% we still achieve 99% of the benefit. BUT WE TREAT THEM LIKE STEP goals.

We treat our challenges as if they have the same reward profile of motorcycle stunts when really they are more like cash grab booths. This isn’t always a bad thing. Believing that you are taking on a STEP challenge is highly motivating – it’s a great tool to get the best out of yourself … until it isn’t.

If you ever feel that you are NOT going to be successful, then your motivation plummets. It can mean that you won’t take on a goal that you might succeed at, and you quit early on challenges you should persist at.

You are also much more likely to give yourselves a vicious psychological kicking when you fail at a STEP goal.

IN SUMMARY

I’ve argued that we will make better decisions about which challenges we take on and which challenges we continue on if we are clear about WHY we are taking on the challenge – about the benefits we hope to get.

I’ve argued that we have an unfortunate tendency to believe that we get all the benefits only when we reach the target. When in fact, much of the time, the more effort we put in the better off we are.

This false apprehension of the situation isn’t always bad. Increasing the pressure on ourselves, can lead to higher motivation and better performance. But there is one big caveat – performance increases only as long as you think you can still reach the target. If you ever think you can’t then motivation tanks and effort stops.

In the next blog post I look at putting this distinction to work. It turns out that it’s surprisingly helpful. I’ll be suggesting ways to keep motivation up even when it looks as if you’re going to fall short. When you should take on a much larger goal, and how you can safely approach doing a backflip on a motorbike, or any other challenge that might leave you broke and broken.