This is the fourth in a series of blog posts about achieving more by rethinking failure. In this post we see how you can overcome the motivational slump characteristic of tough STEP goals, how to remove the possibility of failure, and how to maximise RAMP goals.

We had tried catching them but nothing had seemed to work. The effort just to keep up was immense and it was looking increasingly like we were putting ourselves through hell for no particular good reason. There was a huge temptation to stop trying as hard and coast into the finish. After all winning is everything, and no one cares how far behind second place comes.

This is classic STEP thinking.

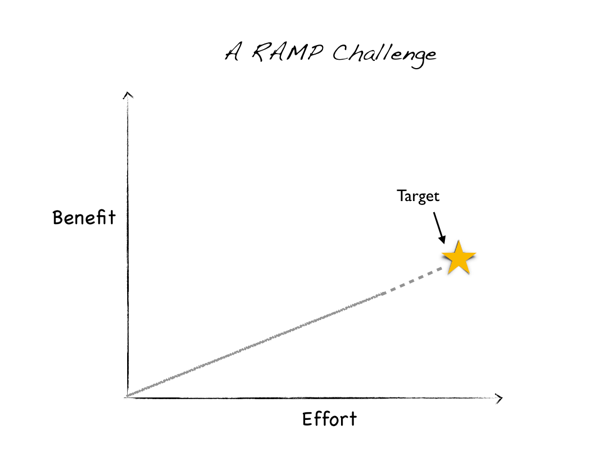

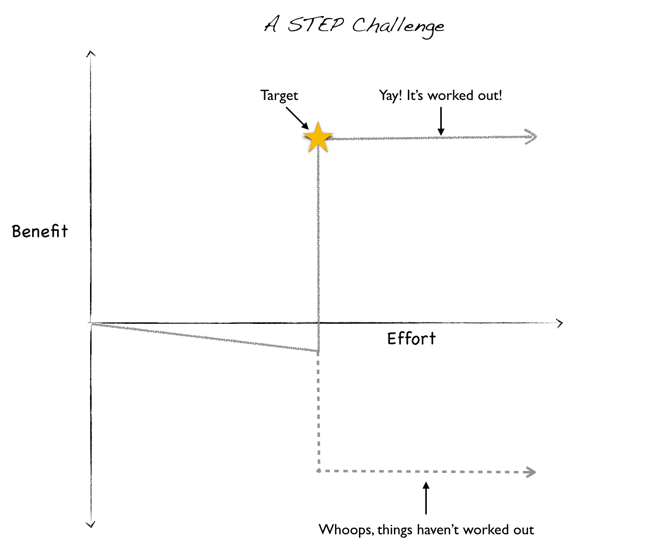

In the last blog I introduced the idea that challenges are RAMPs or STEPs based on when you get the benefits of taking on the challenge. When more effort leads to more benefit (like going on a diet) then it’s a RAMP. When it’s all at once, like defusing a bomb, it’s a STEP.

In this blog we’re looking at how you might use this idea to help you figure out:

- if you should continue when you’re in the middle of challenge and it doesn’t look like you’re going to make it

- if you’re wondering if you should even take on a challenge because you might not complete it

- if you should even take on a tough challenge

- how to approach your challenge when it’s a RAMP

- how to deal with the risk of serious failure if your challenge is a STEP

What to do if you have a STEP goal and feel your motivation is about to switch off:

The first problem with STEP goals is their the ‘all or nothing’ nature. If you think that you won’t make the target in the timeframe then you won’t take it on. Or if you are underway, and start to have doubts, then your motivation plummets and you’ll probably bail early.I have a coaching client that wanted to lose a certain amount of weight in a certain period of time. He began to lose weight … but not fast enough. Feeling like he was going to miss his target - he stopped - even though he was losing weight. He couldn’t see that he was on a RAMP, the more he did the better off he was. His self-imposed deadline was an illusion.

You see this motivation collapse in sport. After a closely fought first half a team comes out for the second half, lets a few points in, loses confidence and then the landslide begins.

Happens in tennis too. You might have seen Nick Kyrgios at the Shanghai Masters. Nick made up his mind that he wasn’t going to win and stopped trying. When he returned the ball at all he just pat-a-caked it back over the net. It’s a very strange thing to watch. Not surprisingly he was booed and heckled by the crowd.

But from his point of view he’s being completely logical. Let’s assume that he is correct in that he can’t win the game. Why shouldn’t he just throw it? Why shouldn’t he save himself for the next game. What is he missing?

The answer, I believe, is that he thinks the match is a STEP, but really it’s a RAMP. He thinks that if he can’t win then there’s no point being out there. When in reality the better he does, the closer the game is, the better off he is. By failing to provide entertainment to the crowd he reduces his brand, his future appearance fees and alienates himself from his fans and his sponsors. Not to mention butchering his self-respect.

So his thinking is clearly dysfunctional right? You wouldn’t be like that would you? Do you play like Nick Kyrgios or Roger Federer when you look at your filing tray? When you think about tidying the garage?

The first thing to do, when your motivation is failing is to check your assumption that your challenge is worthwhile if and only if you meet some arbitrary target. Are you getting nothing from persisting?

But what if you really are in a STEP situation? You’re half way through the year and it’s clear that, barring a miracle, you’re not going to make your annual sales budget. When it looks like all the additional effort you’re going to put in is now going to be a waste of time because you can’t salvage the situation.

Then it’s time to widen the goal posts a bit. Time to give yourself more than one way to win. Can you make the challenge less like a STEP and more like a RAMP? Here’s what I mean.

Trailing second, only 10 days out from the end of the trans-Atlantic rowing race, Jamie and I had a long discussion about what we should do. Do we keep trying to win when we could just take it easy, cruise to the end and look like we could have come first if we had been so uncool as to want to try hard?

We realised that what we needed to was to give ourselves another goal that was obtainable. In fact, to have a cascading series of goals, each a little less ambitious than the last. Here was our plan

1. We were still going to try to win the race. If we couldn’t win the race then our goal would be to;

2. Come second by so close they hadn’t had a chance to have a shower (psychologically a dead heat). If not that then we would;

3. Try and break the old world record. If not that then we would;

4. Leave everything out on the water, they would have to scoop us up out of the boat at the end – because we didn’t want to take it easy and then find out later that something had gone wrong with their boat and that we could have won if we had kept pushing.

This way if it looked like we weren’t going to make the first goal then we could just move to the next one -we still had reason to keep putting in maximum effort. We’ve turned our STEP challenge into a (lumpy) RAMP.

You don’t have to wait until things are going off track to come up with new targets. You could just set ‘Good’, ‘Better’, ‘Best’ targets at the very start. Sometimes companies set their staff ‘goals’ and ‘stretch goals’ for the same reason.

Or we can do away with targets all together. That’s right, you read correctly. Goals without targets (or targets without deadlines). This is an ‘improvement goal’ and that’s a topic for an upcoming blog post.

When you’re wondering if you should take on challenge because you doubt if you will be able to complete it?

So you want to clarify by asking yourself what the situation is by asking:What do I get out of taking on this challenge? What exactly are the benefits and when do I start getting them? Does it really matter if I don’t quite reach my target?

You might be surprised by how often the answer is no, it doesn’t matter. Your challenge is a RAMP, in which case, you should probably go for it.

I could have used this approach when I was having that dilemma of whether or not I should take part in the Tarawera 100k ultramarathon. Instead of going backwards and forwards on it I could just have asked if this challenge was a RAMP or a STEP. Let’s do that now.

What are the benefits? Why am I doing this? To see if I can run a 100ks sure, but also to run through some beautiful scenery, and feel the excitement of being part of an event. Also, there is nothing like having a race to focus your training as well. I will run farther training for this race then I will in the race itself, so that’s where the real benefit lies.

So does it really matter if I fall short? Well, no. Every step I run past 42 km would be a new personal best. There are no penalties. No public shootings of recalcitrant runners. If I want to pull out I just hobble to the next aid station. This challenge looks like a STEP but it’s a RAMP. So why not take part?

Deciding whether or not to take on the race on the basis of whether I may or may not cross some artificial target of 100km would have been completely wrong headed.

How to approach your goal it if is a RAMP

Why not see if you go even bigger?I met an actress who said her goal for that year was to get an EGOT – This is an Emmy, a Grammy an Oscar and a Tony. Only a handful of people have every achieved this, and it’s normally the work of a lifetime. So to do it in a year is bonkers. But if she understands that - then it’s no problem.

This is because RAMP and STEP goals have different motivation profiles.

With STEP goals you’re motivated by the end getting closer. You’re in a permanent state of lack until you reach the target. You start off anxious and you stay anxious until success becomes assured. How far you’ve come doesn’t count for anything because the benefit can’t be banked until you finally reach your goal.

With a RAMP challenge – you are also motivated by the gap between your current position and the target, but you’re less anxious because you’re getting better and better off the more effort you put in. You’re climbing a cliff but in this case the ground is helpfully rising up underneath you.

Unfortunately, because of our perverse human nature, not having so much at stake means that sometimes our motivation in this type of situation is not quite as strong.

One way to compensate then, is to set higher and more exciting goals. So back to our actress. If this crazy goal motivates her more than a lesser goal, and if at the end she is going to judge herself by how much progress she’s made rather than how far she has left to go, then it’s an awesome goal. If your challenge is a RAMP it doesn’t matter how big it is as long as it motivates you.

A year ago I met a guy who was very overweight, and we got talking about goals for the year and he said that he wanted to lose weight, but that just having a lower number on the scales wasn’t really inspiring for him. Which makes sense. When you think about it, unless you’re actually breaking floor boards there isn’t much benefit in losing weight. Nobody wants to be lighter (would you be happier in space?) no, they want to look better, move easier and live longer.

So he decided that he would make that his goal. This big bellied couch potato decided would train for an ironman in two years’ time. That’s a 3 k swim, 160k bike, then a marathon. That it was hopelessly ambitious didn’t matter. It was very exciting to him. So he started training.

And it’s working, a year later he’s looking ripped. And even if he doesn’t complete his ironman, or even get to the start line, he’s still lost a lot of weight and is much, much fitter.

The great thing about a RAMP goal - you can fall a little short and have nothing dramatic happen. The downside is that a RAMP challenge may not have the same level of white knuckle anxiety that we sometimes find motivating. So why not see if making the challenge larger makes it more exciting?

How to approach your challenge if it is a STEP and the consequences are very real and distracting

Let’s say you’re lining up to do a back flip on your motorbike and you’re worried about landing on your head. Or you’re thinking about opening a new café but are worried about going bankrupt. Then there are things you can and should do to remove that possibility of catastrophic failure.To be successful you should not have to risk everything on a single attempt. Very often it’s going to require making multiple attempts, adapting each time, before you become successful.

Broadly speaking there are two ways to do it- reducing the chance of failure or reducing the consequences.

1. Identify the weak spot and strengthen it

Preparing for the trans-Atlantic race I took a great interest in any stories about things that had gone wrong with row boats at sea. I heard for example, that a crew had put out their sea anchor in rough seas, only to have the rope pull off the anchor point on the bow the boat. It hadn’t been made strong enough. So I had our boat builders reinforce that section so much that our fully loaded boat could have been dangled from that point.

What’s going to ‘break’ on your challenge? How can you reinforce that?

2. Build your skills - Practise in a safe way

Stand-up comedians, quite naturally, hate to bomb. The problem is that even the most experienced comedian can’t guarantee that the audience will love a new joke the same way that they do. So when a comic has a big show coming up what can they do to make sure that it goes well?

They practise in the suburbs. They go to the late shows at lesser known, dingier clubs. They try a joke out 2-3 times and, if it falls flat, then they bin it.

It’s the same for practising backflips on a motorbike. How do you think they train for that? They don’t just line up the young guys and the ones that we see are the ones that have survived. Instead they practise by jumping into a nice, big, fat, safe foam pit.

Does your challenge’s success rely on your skills? How can you practice safely? I’ve given various versions of my speeches several hundred times. I still practice, especially new material, and especially the start. My rule is that I’m only as good as my third best rehearsal. So I keep practicing until that’s really good!

3. Benchmarking

At a recent workshop I met a guy who was trying to figure out whether he should become a commercial pilot. He was already a private pilot, but he didn’t know if he should commit to making the next big step given the huge investment in time and money that’s involved. Specifically, he was just worried that he wouldn’t pass the practical and theory exams. So for him this was a STEP goal. How could he take the risk out of it?

One way is to benchmark himself against people who had passed and failed. Knowing the average pass rate would tell him something. That would be a start, but he could do even better.

I suggested that he ask a couple of his most senior instructors about his flying ability. Based on their experience of pilots who had gone on to be successful and unsuccessful how did he compare? Was he in the definitely pass, definitely fail, or in a grey area in-between? If they didn’t have a good idea now, then how many more hours would it take before they could make a better prediction?

There are two tricks for benchmarking.

1. Find examples that are most like your situation

2. Look at failures as well. This is very important.

Let’s say that you want to open a café in a certain street. You have been inspired by another café in a nearby street that is clearly doing very well. Before you invest a cent wouldn’t you want to know what the chances of your succeeding are? For example if you found out that 60% of new cafés in the city close within two years and that all the cafés on your intended street had failed over the last 5 years then you would want to be really sure that you knew why you were going to be different?

It’s not enough to just look at the winners. Many business books make this mistake. It appears to make sense to look at companies who have succeeded and see what they have in common. But it’s meaningless unless you can also show that the companies that failed didn’t also have those characteristics. For example, often companies that succeed look like risk-takers. So the lesson then is if you want to succeed you need to take risks. But hang on. I bet that companies that failed look like risk takers too! So is the lesson to take more risks or to be more lucky?

When I was thinking of taking part in the trans-Atlantic race I certainly did some benchmarking and looked very hard at the background of people who had successfully made the crossing. You might think that it was only for hard core extreme adventurers, ex-military and so on. Nope. Turns out that husbands and wives had competed, mothers and sons. People who were really unprepared, who had built their boats in the bottom of their garden, had managed to get themselves across. Knowing that was hugely motivating for me. If they could do that, I could do it too!

4. Put less on the line – experimenting

Sometimes you just don’t know before you start whether or not an idea will be successful. It can’t be figured out from a spreadsheet, it has to be discovered. In that case, you might be able to experiment.

By experimenting I mean testing out your key assumptions on a limited scale, where failure is contained and expected. For example, before you launch your new business can you launch a pop-up store? Can you test demand online?

Before I took part in the trans-Atlantic race I thought I better see if I liked being out in the ocean. So I helped deliver a yacht from Auckland to the Bay of Islands. It wasn’t really the ocean, but at least I was on the water. I found that I didn’t mind being out on the waves but was very prone to sea sickness. Which was good to find out in advance!

5. Get a safety net

Most of the advice above focuses on avoiding disaster. But sometimes the risk comes from factors that you just can’t control. You might be the world’s best tight-rope walker but you can’t control a gust of wind. Does that mean you should give up on your dream of walking across the Niagara falls? I thought it did.

When I found out that six boats, twelve crew, had been lost trying to row across the Atlantic over the last 100 years I thought it was a real deal breaker. It was little comfort to me that all the boats had been found intact afterwards. And what had clearly happened was that a rogue wave had knocked the crews off the boat. I couldn’t control the ocean. I didn’t want to take a gamble with my life. My motivation plummeted.

Then I found myself talking on the phone to a guy who had just come back from a trek in Antarctica. He was a friend of a friend and someone said ‘You’re thinking of doing stuff like this, why don’t you call him up?’

So I called him up, I thought I should keep the first question broad, so I asked, ‘What’s it like down there?’.

He said ‘It’s ok.’

I thought, ‘Right. He’s one of those tough adventurer types, I better be specific!’ So, I asked, ‘Isn’t it cold?’

He said, ‘You know it’s going to be cold, you take warm clothes.’

I was stunned. I thought you had to get frostbite. It was some kind of law. But instead what he was saying was if I could see that something bad was going to happen, then I could do something about it.

Either to avoid the worst case, or if the worst case happened to reduce the impact.

It was true that I couldn’t predict when a rogue wave was going to hit. Or even stop myself from being swept off the boat by a ton of water. But I could make sure that I was tied on.

Not being able to control the possibility of failure doesn’t mean you quit on the challenge – all you have to do is make sure that you have a safety net. Some failsafe Plan B that makes the consequences of disaster survivable.

So that’s 5 ways to reduce the risk – there will be other ways. The key point is that just because you can find ways things are going to go wrong that doesn’t mean you have to abandon your challenge. There are always ways to reduce that risk.

Step or ramp?

Dilbert creator Scott Adams gave a blistering critique to the way that we normally approach goals.‘Goals are for losers. That’s literally true most of the time. For example, if your goal is to lose ten pounds, you will be spend every moment until you reach the goal – if you reach it at all – feeling as if you were short of your goal. In other words goal-oriented people exist in a state of near continuous failure that they hope will be temporary.’ – 'How to fail at almost everything and still win big'.

He’s talking about the traditional approach of treating all goals as if they are STEPS. Now you know better. I’ve found this simple distinction between STEP and RAMP challenges to be very useful, and I hope you do too.

Just this morning, I walked past my pile of filing for the hundredth time. I didn’t take on the goal of clearing the tray because I can’t see myself completing it. I want to ‘succeed’ at this task. I want to do a little work and then look at an empty tray and get that delicious dopamine blast of success. But since it is impossible to clear the tray then there is no point starting, because I don’t get any benefit unless the job is done.

This is STEP thinking – and it’s complete nonsense, and now you know what to do. I don’t have to complete this task, I just have to start it. If I put away one item I’m better off. What’s so hard about that? I don’t have to ‘succeed’ at this goal, any effort will produce some benefits. It’s cash just waiting there to be picked up.

But what if you take on a STEP challenge and you do fail? That’s the last missing piece and that’s what we’ll be looking at in the next blog.